My grandma, the tricentennial woman |

En español:

|

|

|

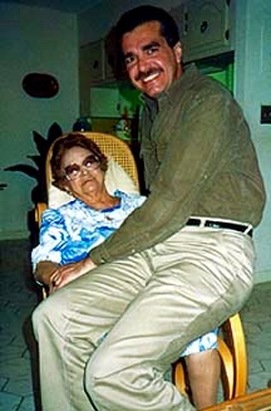

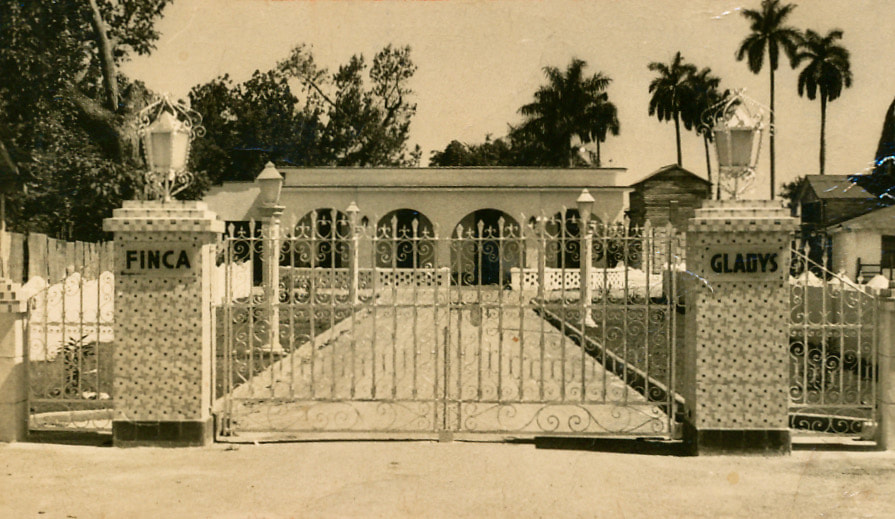

Editor's Note: Record columnist Miguel Perez recently went on a journey in search of his family roots. He didn't have to go back to his native Cuba. No one there could tell him the things he could learn in Miami — from his 101-year-old grandmother. January 2, 2000 — The wrinkles on her face are few for her age. Her smile and friendly disposition could make you swear she is at least 20 years younger. Her memory slips a little, but she still has the wit and sense of humor of a dynamic young woman. Yet Friday was her 101st birthday. Her name is Ramona Ofelia Martinez, a grand old lady who lives in Miami. I love her dearly. She's my grandmother. With arthritis taking its toll, her fingers and toes are a little crooked. She moves around slowly, with the aid of a walker. But to me, she still looks absolutely beautiful. While most of us are thrilled to be entering our second century, my dear mama, born on Dec. 31, 1898, is excited about beginning her third. She was 1 year old the last time the calendar rolled over to double zeros. My grandmother is looking forward to the new millennium. She is quite aware that she's now a tricentennial woman and that she outlived the entire 20th century. She's aware, too, of the purists who argue that the 21st century doesn't really begin until next year, and she jokingly tells you "not to worry, because I'm planning to be around for that." She wears her age like a badge of honor. "Everywhere I go, when people find out how old I am, they want to know how I did it," she said. "What's the secret? I tell them I didn't do anything special, that I'm still alive because it's God's will." But it's her God-given youthful personality, her unwithering laughter that maintains her thirst for living. "Make sure you write wonderful things about me," she joked when I visited her "Little Havana" apartment recently. "Say you found me cheerful and smiling." She didn't have to say that. I don't remember her any other way. I visit her often. But this time I went there with my notepad, in search of my roots, knowing that my time is running out to learn things about my ancestors that only my grandmother remembers. I came back in awe of how much has occurred in her lifetime. Hers is the story of the 20th century. Born and raised in La Salud, a small rural town in Cuba's Havana Province, she still remembers a time before cars and airplanes, before radio and television, before electric light and running water. "It has been a century of incredible progress," she said, "and I have seen it all." Sitting on a rocking chair I gave her on another birthday some 15 years ago, she marveled over the miniature screen on my digital camera, displaying her photos moments after they were taken. "What else are they going to come up with?" she asked. Then she paused for a moment and smiled. "During my lifetime," she chuckled, "I must have asked myself that question a million times." At 101, she wonders about the future. "Can you imagine what things will be like 100 years from now, the new inventions that will be realized in the next century?" she asked, and then proceeded to answer her own question. "Believe me, you can't — no one can," she said. "When I was young, I never thought I would get to fly in an airplane. But I did. And seeing a man land on the moon, oh no, that was unimaginable. But I saw it." She was born at a time that marked the emergence of the United States as a world power, right after the end of the Spanish-American war — in the country where most of the war was fought. She was already in her mother's womb when Teddy Roosevelt led the Rough Riders to victory at San Juan Hill, and when Cuban patriots won independence for the island. During her adolescence, between January 1899 and May 1902, Cuba was run by a U.S. military government. She was 3 years old when American forces left and Tomas Estrada Palma was elected the first president of a free Cuba in 1902. "I was too young to remember, but I do recall that later in school I learned how significant those years were for Cuban history," she said. She was almost 5 years old when Orville Wright took to the sky at Kitty Hawk in 1903. But as a child in La Salud, a small village mostly populated by poor farm workers, she pre-dated most of today's modern comforts. "We had no electricity," she said. "We lit the house with kerosene lamps. We cooked on charcoal stoves, and if you didn't have your own well, you got your water from a spigot-wagon that came around and filled our buckets." The daughter of a bodega owner, with three sisters and two brothers, in a period of war recovery, she experienced some tough times as a child. She met my grandfather — Miguel Martinez — just about the time the United States was entering World War I in 1917. They worked together in a cigar factory. She was a teenage beauty who strung tobacco leaves from strings and hung them to dry. He was four years older, a dashing "reader" who stood on a balcony and read newspapers and novels to the workers — in the days before radio. "He was very handsome and quite a talker," she recalls. They were married a couple of years later. He went to work as a clerk in the town's courthouse. But raised in poverty, he was determined to become a landowner. She stayed home to raise a family. It was expected in those days. During North America's Roaring 20s, my grandparents roared toward their goals. He worked in the courthouse until midday and on the farm fields until nightfall. By the 1930s, he had purchased three small farms, and she had given birth to three daughters, including my mother, Lilia, who died in Miami in December 1998. They named their farms after their daughters. Those were the good days for my ancestors. But life was not without tragedies. A few months after giving birth to my aunt Mirta, my grandmother suffered severe burns to most of her body, when her mentally ill mother committed suicide by setting herself on fire. She threw herself on her mother, trying to save her, and nearly lost her own life. A few years later, shortly after my aunt Gladys was born, my grandfather purchased his third farm and named it after her. La Finca Gladys, with its large country house, beautiful rose garden, and impressive two-lane entrance near the center of town, was to become my childhood home. It was there that in the early 1950s, when I was a toddler, my grandfather bought the town's first television, "and practically the whole town came by our house to see it," she said. The 1930s and 1940s were times of political unrest in Cuba, with various dictators and puppet presidents ruling the island. And the 1950s, after many years of tireless work in agriculture, my grandfather had acquired considerable wealth. His sugar cane, avocado, papaya, and potato crops grew larger and more fruitful. They got to travel abroad, visiting the United States and Mexico. But my grandfather worried about how his business interests would be affected by political instability. In the late 1950's he bought arms for the guerrilla rebels, led by Fidel Castro, who were fighting to overthrow the Fulgencio Batista dictatorship. My grandmother was too busy to worry about politics, first raising a family and then splitting up with my grandfather — "he was a flirt" — and moving to Havana with my aunt Gladys in the early 1950s. They were permanently separated then, but never divorced. On my grandmother's 60th birthday, the last day of 1958, as the world welcomed the New Year 1959, all of our lives took a different course. On that New Year's Eve, most Cubans got their most cherished resolution: freedom. My elders were all ecstatic. But it was short-lived. Fidel Castro soon became just another dictator, one that could prolong his stay in power by introducing a different totalitarian ideology. "I never cared too much about politics until Fidel came and took everything we had worked so hard to obtain," my grandmother said. Soon, many of their properties were confiscated. My grandfather was jailed three times, just for protesting. La Finca Gladys is now a Castro military installation. Weeds grow in the garden where my grandmother once nurtured beautiful roses. Unlike many wealthy Cubans who brought much of their money to the United States, my grandfather, stubborn as a mule, refused to divest his businesses in Cuba. He didn't think Castro would last. He was expecting to return in just a few months. He had no intentions of dying in the United States. I was already in Miami, with my brother and parents, when my grandparents came to join us March 29, 1963. They left Cuba with three sets of clothing and not a penny to their name. For the first time since the cigar factory, grandmother was forced to work outside her home — in a South Florida tomato packing plant. While many younger Cubans were able to start over, for my grandparents it was too late. They had already reached retirement age when they got here. Thankfully, my aunt Gladys, who came with them, was able to obtain her teaching credentials. Now a retired Miami public school teacher, she still shares the Little Havana apartment with my grandmother. In the early 1970s, still waiting for Castro's fall, my grandfather suffered a massive stroke that left him bed-ridden for several years. My grandmother nursed him until he died in 1979. He was 84. But my grandmother survived to see the fall of communism almost everywhere except in her own homeland. She survived both of my parents, but the only one she really wants to survive is Castro. "It's the dream of all Cuban exiles," she said. "To see Cuba free before we die." And she has survived other battles. A few years ago, intimidated by draconian legislation that threatened to deny health care and other benefits to elderly immigrants, she accomplished yet another milestone, becoming an American citizen. "You live on and on, and you don't realize it," she said, "and before you know it, you're 100. But the truth is I've enjoyed good health most of my life. And still today, my blood pressure is fine, and I don't have a cholesterol problem." At 101, the only thing she complains about is not being able to eat whatever she pleases. Just a few months ago, after encountering stomach problems, she was ordered by her doctor to follow a healthier diet for the first time in her life. "They don't let me eat anything," she complains, referring to the vegetarian meals on her dinner table nowadays. "You know I like to eat," she chuckles, "and for my first 100 years, I ate everything. I guess I've eaten enough of the good food, but I still miss it." The seasoning in typical Cuban food makes her sick nowadays. But she still hasn't given up an occasional sip of strong and sugary Cuban espresso coffee. "Salud," she says in Spanish, raising her coffee cup and offering a toast "to your health." She devoted her life to her family, and with her strength of character and cheerful disposition became the crutch on which the whole family could lean on. She was the sponge that absorbed all the family problems. We still go to her for advice, not only because it makes her feel like she still has a role in this life, but because we value her judgment. A deeply religious woman, she credits God for all the good things in her life. "I count on Him for everything," she said, showing no fear of death at an age when it is expected. She believes there is a wonderful afterlife. "I believe that if you do good in life, if you believe in God, and you are a good person, you go to heaven," she said. "And I believe I've been good," she added, with another chuckle. "We'll see each other there some day." As a devout Catholic, she never took her faith to an extreme. I always admired that about her. She was always ready for a good party — still is — especially if you give her time to make herself pretty. A proud woman, she never allowed anyone to take her picture unless she was ready. It's what keeps her young. "I just dyed my hair," she said, running her fingers through her deep-red hair. "What do you think of this color?" During my recent visit to Miami, family members took her to dinner at a Mexican restaurant. She surprised everyone by singing with the mariachis. "I can't believe how all these lyrics are coming back to me," she said with a laugh. On our way home, I reminded her of something that I had neglected to mention during dinner, so as not to dampen our spirits. By coincidence, I told her, it turned out that the family reunion had occurred on the first anniversary of my mother's death. "We had such a good time, and yet today is the anniversary," I told her, feeling a little guilt. "Are you kidding?" my grandmother asked me, once again demonstrating the faith and disposition that keeps her alive and beautiful in my eyes. "Your mother probably arranged the whole thing." Originally published in The Record |