For Elderly Exiles: No home, only hope

|

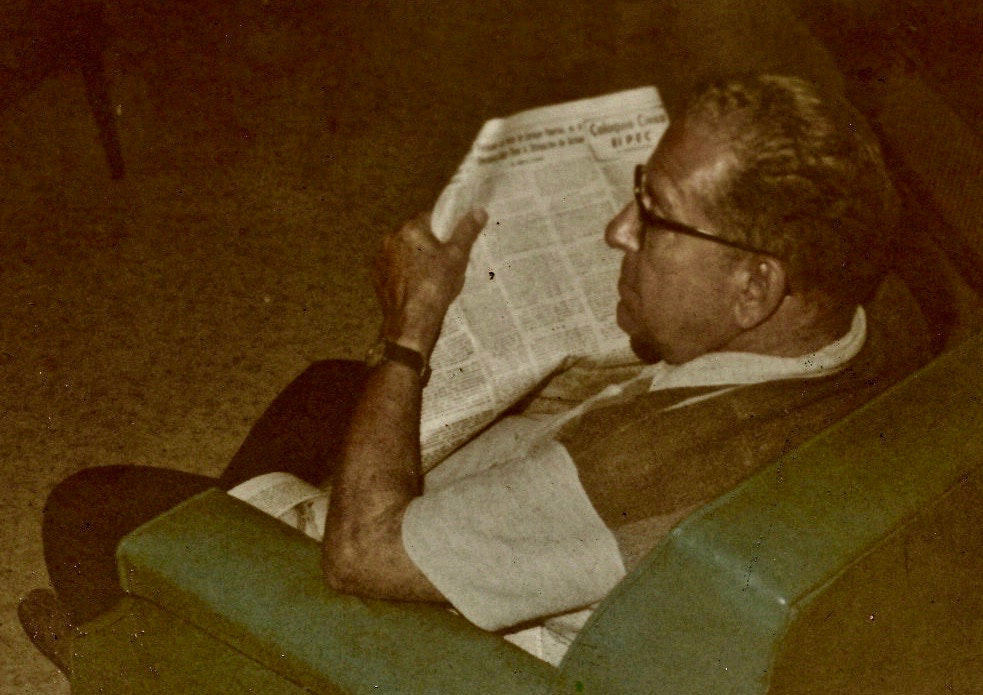

July 6, 1975 --Editor’s Note: According to a recent study, many older Cubans suffer problems magnified by language barriers, economic instability, limited transportation, loneliness, expensive housing, and poor health. Herald Staff Writer Miguel Pérez describes the problems through the story of one elderly Cuban, Anastasio Miguel Martinez — his grandfather. As though his life were already over, the old man lies defenseless on a bed, not knowing whether he's dead or alive. He can still breathe, but it's not the sweet smell of sugarcane fields. He can still see, but not enough to recognize the woman he once loved. He can still hear, but sometimes it's not the language he once knew. Anastasio Miguel Martinez, 80, is a Cuban exile, one of many older Cubans who came to America abhorring oppression and seeking freedom — but only for a short stay, "to go back tomorrow or the next day," and with no intentions of dying here. Time has finally caught up with Miguelito, who was born a poor country boy in the small town of La Salud, Havana province, and became a millionaire after many years of tireless work in agriculture. Since he suffered a stroke almost two years ago, the left side of his body has been paralyzed. His doctor compares his mentality with that of a six-month-old baby. Miguelito is no longer self-reliant. Living on memories of a brighter past, Miguelito spent more than 10 years — before he suffered the stroke — reading newspapers, taking an occasional stroll to the corner grocery store, believing that the U.S. government would not tolerate a Communist regime 90 miles from its coast, and praying to Mary, "Our Lady of Charity," to grant him a quick return to Cuba so he could resume his interrupted life. In his burning desire to return to his homeland after long and fruitless years in exile, in his loneliness for not speaking a language which could allow him to devote his energy and expertise to society, and in the problems he has endured in welfare lines, hospitals and nursing homes, Miguelito typifies thousands of older Cubans who are living their last years in Dade County, with hopes that someday they'll rest in peace, in Cuba. Latinos over 55 years of age, represent 17 per cent of Dade's total Spanish-speaking population and 16 per cent of the county's entire elderly population, according to a current federal government study on Dade County's Spanish-speaking elderly. The study, prepared for the Cuban National Planning Council and financed by the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, said that "forced from their homeland, the Cuban elderly in particular have suffered a trauma which few others have experienced. Consequently, the normal suffering which often accompanies aging is magnified for these poor people." Miami-Dade Community College sociology professors Dr. Juan Clark and Manuel Mendoza, who conducted the study, said older Latinos in Dade are plagued by language deficiency, loneliness, poor health, expensive housing, limited transportation, economic insecurity and family neglect. For the study, Clark and Mendoza selected a scientific sample of 120 Cubans, nine Puerto Ricans and 22 other Latinos 55 years and older to represent the estimated 55,000 elderly Latinos in Dade. Miguelito was not part of the survey, but he would have agreed with the majority of elderly Cubans who wrote "a Communist-free Cuba" when asked for their major aspiration. That was his whole life, day in and day out, seven days a week. The hope that he would return to Cuba gave Miguelito reason to get up and go on each day. He read newspapers almost constantly, in English and Spanish. In Cuba, Miguelito had taught himself to read and write the English language, but he could not pronounce or understand a spoken word of it. Everywhere Miguelito went, he took a small transistor radio with him. He was always listening to Kissinger's last word on Havana, and Havana Radio's last word on Cuban politics. As a former sugarcane grower aware of the importance of sugar to Cuba's economy, Miguelito kept close tabs on Castro's ill-fated sugar crops, always hoping they would be even more disastrous than in the previous year. When Miguelito's grandson enrolled in a Dade County elementary school in 1963, Miguelito said it was a waste of time. "What's the use in going to school here," he told his grandson. "We're going back to Cuba in a couple of weeks." And when his grandson went to college in 1970, Miguelito's advise was: "You're going to have to transfer to the University of Havana." The study said a generation-culture-gap between older Latinos and their families is caused by the old folks' inability to communicate in English — "a situation which often prevents them from understanding what is happening and consequently, from adapting to the new environment." "The local Spanish mass media tend to reinforce old values and beliefs, and since they do provide a high degree of comfort and reassurance, their orientation does not encourage the elderly to learn English," the study states. In Miami, before he suffered the stroke, Miguelito enrolled in several English courses offered in adult education schools, but he wanted to learn English only so he could use it in his business transactions in Cuba. He didn't think he would need it in Miami. He was not going to be here that long. As Miguelito waited for Castro's downfall, sitting on the porch of a Little Havana home he shared with one of his three daughters and her family, he told stories of bleaker days when he was a poor boy growing up in La Salud, and brighter days when he enjoyed the life of a rich man in Havana. Born April 27, 1895, the son of a poor businessman who bought tobacco from growers and resold it to cigar makers, Miguelito never had sufficient clothes to wear. And he was lucky when he had a good pair of shoes. His father left home when he was a young boy and his mother became a washer woman to support her five growing children. He finished high school while working at several odd jobs, and was given a job as a reader in a cigar factory, where he stood on a balcony and read novels, newspapers and magazines to workers who listened intently as they rolled tobacco into cigars. Most of the listeners could not read themselves, and there was no radio or television in those days. Later on, Miguelito got a job as secretary to the municipal court judge, got married and bought his first farm when he was about 25 years old. He worked until noon at the courthouse and rode his bicycle several miles to the farm everyday. He worked on the fields until nightfall. With the years Miguelito became increasingly wealthy. He bought more farms and employed more workers. His sugarcane, avocado, papaya and potato crops grew larger and more fruitful. But in the 1950s Miguelito also worried about the unstable times created by the dictatorship that ruled his country and the rebels who were fighting in the mountains to overthrow the dictatorship. He made large donations to the Cuban underground to buy arms and ammunition that would help overthrow the Fulgencio Batista regime. He was overjoyed on the morning on the morning of Jan. 1, 1959, blindly believing that the bearded man who as coming down from the mountains, "like Moses," would bring freedom to the Cuban people, and prosperity to his business interests. Unfortunately, things didn't turn out that way. Ownership of Miguelito's real estate properties was taken over by the government and there was talk that soon Castro's agrarian reforms would take control of Miguelito's farms. It didn't take long for Miguelito to dislike Castro. Shortly after the revolution, he was jailed three times, accused of setting fire to his own sugarcane fields to sabotage Castro's ailing economy. During the Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961, Miguelito hid himself at a friends home in Havana and managed to escape before the mass arrests of anti-Castro Cubans. Some of his friends who were arrested then are still serving time in Cuban jails. Two of his daughters were already living in Miami, so Miguelito came to America aboard a "freedom flight" on March 30, 1963, with his wife and a third daughter. They left Cuba with three sets of clothing stuffed in cheap suitcases and not a penny to their name. Most of the elderly Latinos surveyed by Clark and Mendoza said their most important reason for coming to live in Dade County was to be close to family and friends. Health and the climate were also cited as important reasons for moving to South Florida. Many elderly Cuban exiles chose to stay in Miami after they arrived from Cuba. "Up north, the palm trees don't even grow," Miguelito told his family when some considered to a northern city. "Here, we're close to home. We can just hop on a boat and go back when the time comes." However, the study said, finding a decent place to live is not always easy for elderly Latinos. Thousands of older Latinos are on a waiting list to obtain public housing, the study said, with some waiting as long as seven years. Of the Cubans surveyed, 92 per cent live in rental housing, the study said. Clark and Mendoza said elderly Latinos are spread out over the entire country, but primarily concentrated in Miami and Hialeah. They said transportation problems are widespread among elderly Latinos. Miguelito was unable to get around as easily as the younger members of his family. The movies, restaurants, sports events, churches and activity centers were less convenient for him. He depended on his family to drive him where he wanted to go. "This indirectly suggests inefficient mass transit facilities for this group," the study said. It said Latinos "could benefit significantly from programs specifically tailored to serve the elderly's transportation needs." Miguelito never worked in Miami. He had already reached retirement age when he came here. Younger exiles manage to start over. For Miguelito it was too late. He and his wife live on food stamps and a $210 monthly welfare check. The study said 20 per cent of the Spanish heads of households who are 65 years or older live below the poverty level in Dade County. "South Miami Beach, which is primarily known as an area with a heavy concentration of poor elderly Jews, also contains many elderly Latinos who live below the poverty level," the study said. "Most of the old Cubans here were from middle or upper classes in Cuba," said Miguelito's physician, Dr. Federico Dumenigo, who treats some 700 elderly Cuban patients. "They don't adapt to being poor, and they don't see that they really are poor. The majority depend on Medicare or Medicaid." Clark and Mendoza said they focused primarily on Jackson Memorial Hospital, when inspecting the institutions that serve elderly Latinos in Dade, because the hospital is in a high density Spanish area. They said about seven per cent of Jackson's patients speak only Spanish. Translated into numbers, this represents 1,100 in-house patients, 170,000 out-patient clinic visits per year, and 160,000 emergency room cases per year. The language problems at Jackson, the study said, is due to an insufficient number of Spanish-speaking nurses, only five per cent of the total. The study's authors said Jackson hospital officials are aware of the problems caused by language barriers, "and Jackson seems to be doing something to resolve them." They said Latinos favor Pan American and American hospitals because they have the highest proportion of bilingual personnel. Miguelito spent more than a month in Abbey Hospital, where a large number of the patients and employes are Cuban. But Miguelito's family had feared approaching him, before he suffered the stroke, to consider a change in his permanent living arrangements. They knew the alternative of a nursing home existed, but there's a social taboo in Little Havana against placing old folks in nursing homes. Cubans have become saturated with propaganda and horror stories of crimes and hideous things perpetrated against helpless victims in nursing homes. They fear nursing homes lack compassion and decent physical treatment for the old. "The greatest conflict the Cubans face here is not economic," Dr. Dumenigo said. "It's being unable to take care of their own, the conflict of having to put them in a nursing home — that's their biggest frustration." Dr. Dumenigo said that, in Cuba, nursing homes only took care of patients who had no family to take care of them. In most cases, Cuban grandparents in Dade County live with their family, and most families are reluctant to put their parents in nursing homes. Miguelito's relatives, however, found themselves having to work and without any choice but to give the nursing home a try. But they felt bitterness, guilt and fear when they did it. They took him out after a week. "The trend towards increased participation by Spanish families of the nursing home option, as a way of coping with the elderly, is due to economic factors," the study said. "Wives have to work, and there is no one to take care of the old folks. Nuclear families do not allow the sharing of responsibilities that extended families did. Houses are smaller here than they were in Cuba, thus making it more difficult to keep elderly parents at home. Finally, cultural diffusion has led an increasing number of Cuban families to adopt American values." "An elderly person reacts against any changes that puts him in a strange environment," said Leo Allen, director of the Miami Convalescent Home, at 335 SW 12th Ave., where 95 per cent of the 147 beds are occupied by Latinos and 98 per cent of the employees speak Spanish, according to figures given by the nursing home. "It's bad enough having to be in a foreign country, and then having to be in a nursing home where everyone speaks English," Allen said. However, after Clark and Mendoza visited the Miami Convalescent Home in the spring of 1974, they concluded that "there was no homogeneous grouping; patients who seemed to be psychologically sound were mixed with others whose state of mental deterioration was far advanced." Allen said Dade County's 38 nursing homes are improving, overcoming their bad image. And he said nursing homes offer services and skilled care that are not available at home. "In many respects," he said, "it's a blessing to them that there are institutions like the nursing home." "In America there is not yet developed a systematic approach to aging, which allows the elderly to maintain a sense of control over their lives. And placing them in nursing homes where they feel locked in, is probably the worst thing that can occur," Clark and Mendoza wrote. They recommended government financing to operate non-profit nursing homes. "Such funds operated by Catholic nuns in Cuba offered excellent service," the study said. Having a place to go every day, such as senior citizens centers, would help elderly Cubans take their minds off their problems and into a good game of dominoes or a dancing class. But there are few centers for the old in Little Havana, and they are scattered. Clark and Mendoza praised the work of centers that provide a form of "day care activity" for the elderly, but noted that more centers are needed in areas that lack activities for elderly Latinos. One such center is the Little Havana Activity Center, federally funded through the Older Americans Act, at 819 SW 12th Ave., a multi-purpose agency that offers English classes, sewing ceramics, debate clubs, citizenship education classes, a chorus and a drama group. It also provides a hot meal program that serves lunch to about 600 elderly Latinos, in eight locations, for 50 cents or nothing, depending on what the person can pay. "Besides whatever else we can offer them, we bring them together as a family," said Barbara Abel, a social worker at the Little Havana Activity Center. "It brings them out of their loneliness. They are doing something. They are active." Ms. Abel said members receive help with housing problems, loneliness, family relations, health care problems and the use of food stamps. "We fill out any application they may want to have done, we go with them and we are their witnesses when they become American citizens, and we take them to the voting booths." She said she has noticed a new trend in older Cubans wanting to become American citizens so they can vote. The study said 17.9 per cent of the elderly Cubans are American citizens, 53.8 per cent are permanent alien residents and 28.2 are classified as refugees. Clark said elderly Cubans are becoming Americans because they are afraid that if diplomatic relations are resumed with Castro, they may lose their U.S. benefits, such as welfare and Medicare. About a fourth of those interviewed by Clark and Mendoza said they would not return to Cuba after Castro is gone. Another fourth said they don't know, depending on what their children may do. Almost all said they would like to return for a visit, even if they did not want to live there. "All of us want to die in Cuba," said Leopoldo Rivero, owner and operator of the two Rivero Funeral Chapels that serve Cubans in Miami and Hialeah. "Our hopes are that Cuba will be free so we can go back and die there." Records at the Dade Bureau of Vital Statistics show that more than 1,000 Cubans die in Dade County every year. More than 700 have died so far this year. A cross, a map of Cuba and the Cuban coat of arms are carved on a long marble wall in the Cuban section of Miami's Woodlawn cemetery. Dedicated to all the Cubans buried there, an epitaph is also carved on the wall: "In memory of all who because of their love of God, of Cuba, and of the family were united in the altar of the homeland and preceded us in the sacrifice. May God grant them eternal rest, and deny us peace until we conquer for Cuba the victory." Miguelito will not see the royal palms swaying in the Caribbean breeze of his homeland. He won't die in the place where he was born. he was one who waited for the dust of the Cuban Revolution to settle, and like many others, he will end up settled in the dust — in Miami, a place he never called home. |